Indonesia: Long-Term Prospects for U.S. Agricultural Exports

Contact:

Introduction

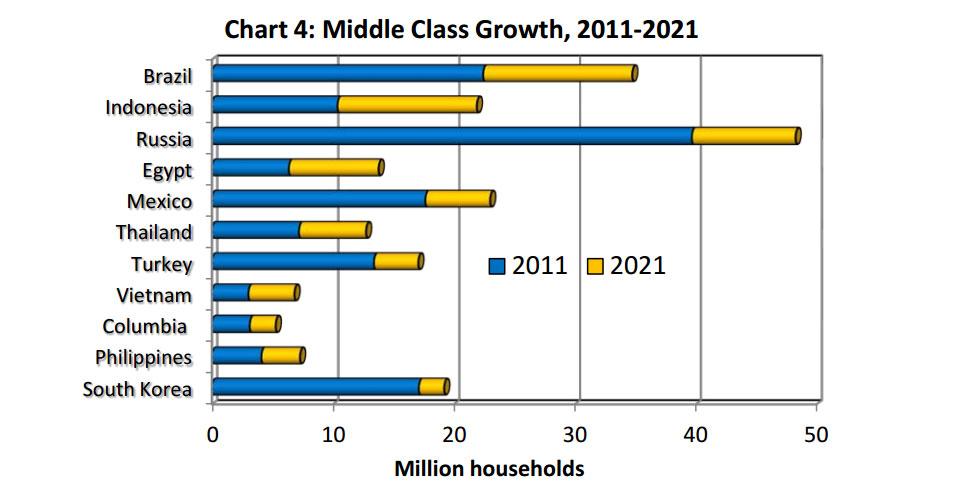

In recent months, the Government of Indonesia has proposed or implemented several new import measures affecting U.S. agricultural exports to that country. U.S. trade officials have engaged their Indonesian counterparts in extensive discussions in an effort to prevent or mitigate the impacts of the new measures. This effort is ongoing and its importance is highlighted by the significant long-term trade opportunities presented by the Indonesian market. By almost any measure, Indonesia is one of the most dynamic growth markets for U.S. agricultural exports. Strong economic performance and rapid urbanization are propelling consumption changes and trade. Despite trade barriers, U.S. exports have been growing at an impressive rate. Robust middle-class growth and evolution in the grocery retail sector support great prospects for future trade.

Country Overview

With more than 248 million people, Indonesia is the world’s fourth most populous country and home to the largest Muslim population. It isthe largest economy in Southeast Asia, with a $1.1 trillion GDP (purchasing power parity). Unlike many other Asian economies, Indonesia’s domestic consumption accountsfortwo-thirds of the GDP. This heavy reliance on domestic consumption, combined with strong macroeconomic fundamentals and a robust policy response, enabled Indonesia to weatherthe global financial crisis reasonably well and to join China and India as the only G20 members to post growth in 20091. Continued strength in consumerspending and investment bode well for sustained future growth, and the country is expected to maintain a real GDP growth rate of around six percent in the coming years2.

Indonesia’s agricultural sector has diversified in recent decades to include an export-led development of cash and estate crops. It is the world’s largest producer of palm oil and coconut, and one of the top producers of rubber, cocoa, and coffee. The rise of tropical perennial crops notwithstanding, the core of Indonesia’s agricultural policy remains food security, defined as self-sufficiency. As the world’s third-largest rice producer and consumer, rice self-sufficiency is a paramount policy goal. Rice is by far the most important food crop, with area planted to rice accounting for 30 percent of total cropland. In addition to rice, Indonesia also has self-sufficiency goals for other crops, as well as poultry and beef. Protectionist policies on poultry (de facto ban on imports) and beef (import quota) are major trade barriers, while domestic production struggles to keep up with demand. Indonesia’s per-capita consumption of beef and poultry is well below neighboring countries, and the expanding middle class points to strong growth potential. The country’s total poultry consumption is expected to double in 10 years. At the same time, domestic production faces major challenges such as lack of land, shortages of feed ingredients, and serious infrastructure deficiencies. Per capita agricultural land is only one third of the world’s average, lagging behind that of China.3 Domestic seaports are outdated and the government has not built a new one in 10 years in this sprawling archipelago state. In addition to constraints in intra-island transportation, Indonesia’s road density also lags behind Vietnam, India, and Pakistan, with transportation costs significantly higher than neighboring countries. The transportation bottleneck means that it is often cheaper and faster to import than to source domestically produced products, as feed mills that depend on domestically sourced material often operate well below capacity. This has created opportunities for imports of feed stuffs. Overall, feed grains, soybean meal, and feeds and fodders account for almost 30 percent of Indonesia’s total agricultural imports.

Trade

Indonesia’s agricultural imports have sustained a double-digit growth rate for the past ten years. The United States is the leading agricultural supplier to Indonesia, with a 17 percent market share. Main competitors include Australia (cotton, wheat, dairy), Thailand (fresh fruit), China (fresh fruit), and South America (soybean meal, cotton).

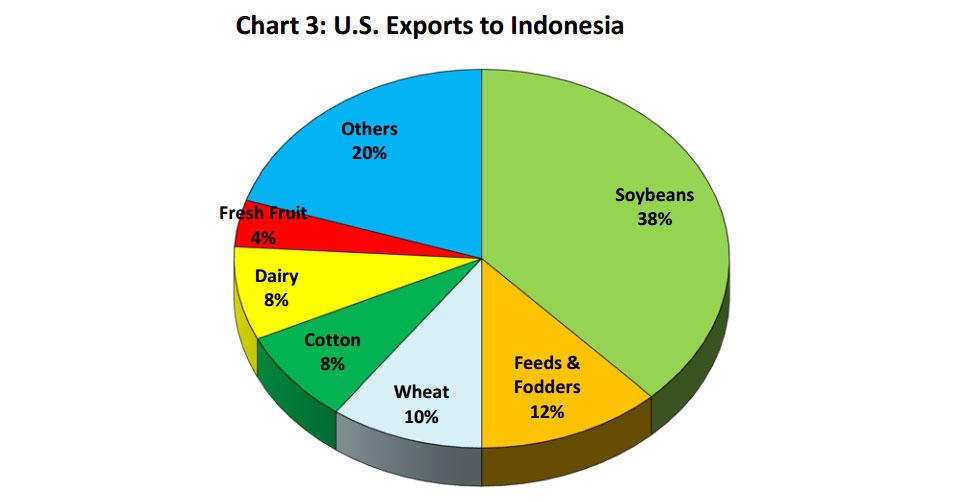

Indonesia is the ninth-largest U.S. agricultural market (Chart 1). U.S. exports have been growing at an impressive rate of 15 percent annually over the past decade, one of the highest growth trends among top markets (Chart 2). However, U.S. products are facing mounting competition, especially for cotton, wheat, and fresh fruit, which is the main reason U.S. exports in FY 2012 slipped 17 percent to $2.5 billion. Soybeans, feeds and fodders, wheat, cotton, dairy, and fresh fruit account for 80 percent of U.S. shipments (Chart 3). Given the diversity of the U.S. export portfolio and the overall strength of the Indonesian market, the long-term outlook for U.S. exports remainsstrong. The following is a closer look at the challenges and opportunities facing U.S. products:

Soybeans: Indonesia is the fourth-largest U.S. soybean market. All soybean imports are for food use, mainly the manufacturing of tempeh, a staple source of protein. Tempeh is made by a fermentation process that binds soybeans into a cake form, similar to a very firm vegetarian burger patty. The United States dominates the market with an 85-percent share, a position that is unlikely to be challenged, as tempeh processors have seen better yields from U.S. beans. U.S. soybean exports to Indonesia have more than doubled since 2007 and, according to the American Soybean Association, a major development in the soybean market is the growing prominence of container shipments. Indonesia is a large exporter of furniture and cloth to the United States, and return container rates have become economical for shipping bulk commodities. About one-third of U.S. beans now enter Indonesia via containers. As more U.S.soybean production moves into the north and northwest, Pacific Northwestshipments are becoming increasingly competitive.

Feeds and Fodders: Indonesia is an important market for U.S. feeds and fodders. U.S. exports have nearly doubled in just five years, led by corn gluten meal, meat and bone meal (MBM), distillers dried grains with solubles (DDGs), and prepared poultry feeds. The Indonesian poultry sector accounts for over 80 percent of total feed demand. Feed mills rely heavily on imported feed ingredients, especially protein meals, additives, and DDGs, for which U.S. supplies are competitive. Indonesia is the largest market for U.S. MBM. Recent trade restrictions on U.S. MBM are expected to be temporary, as the country simply cannot supply enough feed for its bourgeoning poultry sector. Imports of feed products will continue to grow and the United States, as the largest supplier with over half of the market share, is well positioned to continue expanding exports.

Wheat: Indonesia’s wheat importsfrom the world have been growing, on average, 10 percent a year in recent years. The increase has been driven by economic growth, new trends in the bakery sector, and rapidly expanding milling capacity. The milling industry is positioning itself for downstream growth of flour exports. Another factor contributing to higher wheat imports has been rising consumption of instant noodles, which hasreplaced some rice consumption due to price and convenience. The United States faces strong competition from Australian and Canadian wheat, as well as price-competitive Turkish flour. According to U.S. Wheat Associates, Indonesia is increasingly becoming a quality buyer, and teaching bakers and mills about U.S. wheat has helped maintain U.S. market share.

Cotton: Indonesia is the fourth-largest U.S. cotton market. The country’stextile industry employs one-tenth of the total manufacturing workforce and is important to overall exports and GDP. Main export destinations include the United States, EU, China, and Japan. Weakened garment consumption worldwide has led to reduced Indonesian textile exports and cotton imports, while declining cotton prices have also contributed to a drop in trade value. Volatile cotton prices in recent years have also led to large-scale defaults, which disproportionately affected U.S. exports. The United States, which had been the largest cotton supplier to Indonesia since 2003, has slipped behind surgingBrazilian and Australian competition this year, as both countries enjoyed back-to-back bumper crops while U.S. supplies remain tight. The fall in cotton shipments is the main factor behind the overall drop in U.S. FY 2012 exports. However, according to Cotton Council International, the worst of the slowdown in cotton trade may be over, as Indonesia’s domestic demand is expanding, and production lines geared for exports can readily supply the domestic market.

Dairy: The United States has seen strong market growth in the dairy sector. Indonesia is one of the world’s largest importers of skim milk powder. The country’s domestic dairy production could only meet a quarter of its demand, as the industry is dominated by small dairy operations (5–10 cows) with very low yields. At the same time, consumption is expanding rapidly, led by UHT liquid milk and milk powder-imbued snack food and beverages. Indonesia is now the world’s fifth-largest market for non-cheese dairy products, ahead of its wealthier neighbors such as Singapore and Malaysia. It has also become one of the top U.S.skim milk powder and whey markets. In recent years there has been significant investment by a few corporations in large (1,000-3,000 head) dairy farms to meet local demand and export fresh milk to Singapore, which means import potential for U.S. genetics and hay.

Fresh Fruit: In recent years, there has been a meteoric rise in Indonesia’s fresh fruit imports, which are quickly approaching $1 billion. Demand for citrus and temperate fruits has been especially strong. Fresh fruit imports have proved adaptive to both traditional (wet markets) and modern retail formats. China and Thailand dominate the market, while the United States remains the third-largest supplier with a 10 percent share. U.S. sales of apples, grapes, and oranges have all experienced double-digit gains and are even accelerating in more recent years. Since 2007, U.S. exports of apples have nearly tripled, grapes more than doubled, and oranges more than quintupled. However, the strong import growth has led to increased government intervention, and fresh fruits have become a favorite target of Indonesia’s trade restrictions. New import requirements under Regulation 60 include import recommendations from the Ministry of Agriculture (MOA), and importer identification number and approval letters from the Ministry of Trade (MOT). If fully implemented, thisregulation could threaten future growth in trade of fresh fruits.

Outlook

Indonesia has one of the highest growth rates in retail food and beverage sales among developing countries. While traditional retail venues, such as wet markets and small food stalls,still account for 85 percent of grocery sales, modern retail stores have been growing much more robustly, expanding share of grocery sales from 5 percent in 1999 to 15 percent in 2011.4 The number of modern retail outlets increased 13 percent in 2011 alone, as many start to reach second- and third-tier cities.5 Modern retail outlets are wellsuited for introducing imported products, including perishable items and high-value consumer-oriented products. Chicken meat could become a major U.S. export if Indonesia lifts its de facto import ban.6 Beef is another significant market if given fuller access, with a growth potential similar to dairy.7

1 FAS Jakarta

2 Global Insight; Fitch Ratings

3 OECD

4 Dyck, John, Andrea Woolverton, Fahwani Y. Rangkuti. June 2012. Indonesia’s Modern Retail Sector.

5 Euromonitor

6 John Dyck, et al.

7 FAS Jakarta