Despite Continued Challenges, China Offers Huge Potential for U.S. Farm Exports

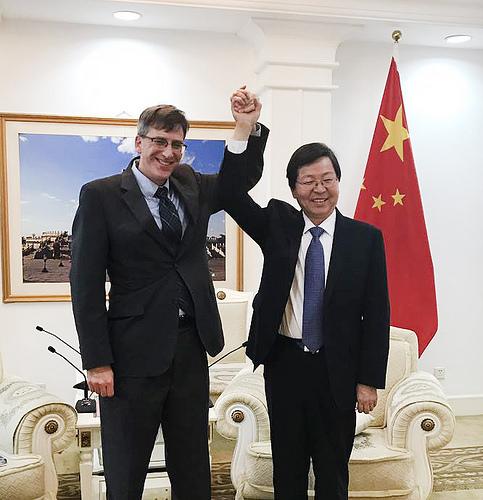

The U.S. Department of Agriculture continues to expend significant resources in China, working to break down trade barriers, promote U.S. farm and food products, and ensure that the country will remain a strong export market well into the future.

Why do we continue to invest so much in China? There are a number of reasons.

First, while trade with China can be challenging, the country is consistently one of our largest export markets. Last fiscal year, U.S. exports of agricultural and related products topped $26 billion.

Second, keeping exports flowing in a market as complicated as China requires a lot of resources. That’s why USDA’s Foreign Agricultural Service has a large team on the ground in China and many more people working on China issues from Washington.

Third, China offers our best opportunity for major export growth in the future. If China makes needed policy reforms this, coupled with expanding demand and domestic production challenges there, could ultimately yield billions in additional sales.

I first started focusing on China in 1994 as the lead agricultural negotiator during the country’s accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO). Back then, it was still a minor market for us. U.S. agricultural exports totaled just $1.2 billion a year, more than half of which was cotton that was processed in China’s textile mills and ultimately re-exported to world markets.

Things have changed significantly since then. When China finally joined WTO in 2001, its GDP was only $1.3 trillion. By 2017, it had jumped to $12.3 trillion, second only to the United States. In 2001, U.S. soybean exports to China totaled $1 billion. By 2016, they topped $14 billion, making China the largest buyer of U.S. agricultural products.

Today, China’s increasingly sophisticated consumers demand a wider range of products. As the country’s economy expands and modernizes, there is a growing appetite for high-quality food – and the United States is uniquely situated to feed that appetite. For example, thanks to Chinese consumers’ surging demand for beef, the country has emerged as one of the world’s largest beef importers, bringing in more than $3.1 billion worth in 2017. China reopened its market to U.S. beef last summer and now high-quality U.S. steak is routinely selling for twice as much there as it does at home. Similar opportunities exist for other consumer-oriented products as well.

Still, doing business in China remains tough. Before it joined the WTO, China strictly controlled trade and often restricted imports with little rhyme or reason. Although it has since made important reforms to its controlled economy, China still maintains multiple, unjustified barriers to access for our agricultural products. There’s a long list of examples. Among them:

- Right now, we’re using the WTO dispute settlement process to address China’s grain policies – both its generous subsidies for domestic production and its continued restrictions on imports.

- Another sore spot is China’s dysfunctional approval process for imports of products developed through biotechnology, which limits trade and thwarts the development of new technologies needed by the world’s farmers.

- China unjustifiably restricts imports of U.S. poultry, and U.S. rice is still not eligible to ship there despite an import protocol signed last year.

- China bans the use of certain veterinary drugs and growth promotants deemed safe under international standards, limiting our ability to sell livestock products.

Given these continued challenges, what does the future look like? As China has grown, so has its reliance on imports. Therefore, it stands to gain the most from reforming its trade regime. Removing barriers to imports will give Chinese consumers more choices, better prices, and a more consistent supply of high-quality products. Overhauling its byzantine system of trade restrictions will bring more efficiency to China’s economy and ultimately deliver higher incomes to its people.

When China becomes a more reliable customer, global suppliers – chief among them America’s farmers and ranchers – will benefit from increased sales. Thus, we need to press China to make these reforms and we need to ensure that U.S. suppliers are ready to serve the market.

When all is said and done, further integrating China into the global agricultural trading system will encourage the development of new technologies needed to feed the world. And when China stands on the side of science and transparency, it will be a powerful model for other restricted economies of how to take appropriate responsibility in the world economy and ultimately reap the benefits.